When Jim Dietz and I discussed the final form that Championship

Formula Racing (CFR) would take, one item in particular stood out on Jim’s wish list - a way to race against the best drivers in history. The vision was to create a Historical Driver system where

different drivers had different personalities, tendencies, and difficulty

levels. It was important that the top

historical drivers in the world would be hard to beat, not just rolling

obstacles.

I wasn’t sure how this would work when I started but this

ended up as one of my favorite parts of CFR. The challenge forced me to consider some core

concepts for creating Automated Opponents.

Below I’ll share what I learned for any other game designers or

tinkerers who might also want to go down this road.

Identify Strategies

My first step in creating an Automated Opponent (AO) was to

figure out what broad strategies I wanted each to pursue. Most hobby games have multiple paths to

victory. Write down those paths and

variations and note which are more popular than others. Don’t

worry if some strategies are not as good as others. If people pursue a strategy, include it on

your list.

Having multiple strategies that an AO can follow allows you

to have multiple AOs that end up doing different things. Some games are just better with a lot of

players so the ability to have multiple diverse AOs can fill in that gap. If only a few AOs would ever be used at the

same time, a variety of AOs will keep each use fresh.

I like an automated system that makes me feel like I am

playing against actual opponents. Real

players have tendencies and goals.

Making popular strategies better represented or more frequent in your AO

design will keep the meta game consistent with or without AOs.

Championship Formula

Racing Example

In CFR broad strategies focus on how quickly to spend your resources. Spend them early for the early lead and try to hold on,

save them for late in the race when everyone else running on bald tires, or spend them evenly throughout the race. I created variations on those three broad

strategies for the AOs in CFR. However, the

popularity of different strategies varies based on the track being used so I

tweaked each AO to pick a different strategy based on the track.

For example, James Hunt will use one of three different strategies: U (more of a mid to late game strategy), Mathy (more of a mid to early game strategy), or Front A (an early game strategy) -- typically in that order. But if the track is particularly suited to an early game strategy he reverses his order of preference. Most of the Historical Drivers in CFR do something similar.

Decision Trees and

Set-Up

Now that we’ve identified the broad strategies that our AOs

will pursue, we need to build a decision tree for each.

For each strategy, figure out what their ideal play would be

and rank all of their other options based on how that will help their

strategy. As a general example, if an AO is pursuing a military

strategy in a game, their first choice for an action on a turn could be to buy the

largest sword, second choice might be to buy more armor, third choice…

etc.

You’ll probably figure out pretty quickly that there are

variations on how an AO could pursue the same basic strategy. Maybe one flavor of military AO buys swords

first, while another makes sure to balance swords with armor.

Don’t forget set-up.

Are there set-up options that might favor one strategy over another that

individual players can choose?

CFR Example

CFR’s basic strategies

lend themselves pretty cleanly to different choices on a given turn. But the reality is that these strategies

exist on a continuum so I ended up creating 10 different strategies along that

continuum:

Front X: uses a ton of resources early and then keeps spending resources until it is in the lead

Front A: pretty much uses resources as much as it can until it runs out

Front B: uses some resources early and then really uses a lot of resources in the middle of the race

Stalking: uses some resources early to stay ahead of most cars, then tries to use resources evenly from then on.

Mathy: will use resources for best effect as soon as possible

Even: attempts to use resources completely the same and evenly throughout the race

U: uses some resources early, saves resources in the middle of the race, then spends the rest at the end

Random: starts out saving its resources, but can switch to spending everything at any time

Back S: spend little at the beginning and then spends more for the rest of the race

Back X: spends little for most of the race before spending everything at the very end

Set-up is also a big part

of CFR. Certain car builds and pole bids

lend themselves to different strategies.

If you want to spend your resources early for an early lead, you might

as well design a car with a high start speed and spend more on the pole bid to start at the front of the grid. Obviously there is a continuum to set-up options as well.

Tactics Change as the

Game Progresses

A diversion into my theory on the three phases of game play,

as illustrated by Ascension. This

structure does not apply to all games but it does apply to a lot of medium to

heavy weight modern board games.

Many games can be split into three

parts: Build the Engine, Run the Engine, Grab Points.

Early in a game, you want to acquire

the tools that you need to pursue your strategy. When I play Ascension, I spend the early game

acquiring cards that let me best acquire more cards or kill off the junk cards I started with. Initially, I don’t care how many points cards are worth, and I don’t care how cool its special power is unless it gets me more cards or

kills more junk.

Once you have your tools, its time

to augment that engine and run it. Twenty points into a sixty point game of Ascension, I switch over to buying cards that

have synergy with what I’ve already acquired.

I’ll pay a little more attention to point values now, but mostly I’m

running my engine. I’m probably not

continuing to acquire more ways to thin my deck.

Near the end of the game, there are

no long term consequences for your actions - it’s all about the short-term

play that helps you win. In the last twenty points of a sixty point Ascension game, I no longer care if the card works with

what else is in my deck, and I stop thinning out junk unless it’s harmless to do

so. It’s all about acquiring maximum points.

Now think about the game for which you are designing your AOs. Are there recognizable phases? How do you measure which phase you are

in. Is it based on the progress of the

game, or a player based metric? Should

your AOs’ decision trees change based on the phase of the game?

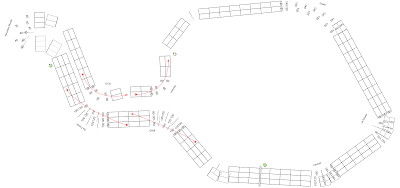

CFR Example

CFR strategies are all

about how your tactics change over the course of the race. I developed two tools to trigger those phase

changes. I split each lap into three

sectors. No matter how many laps are

being run, we can figure out if we are in the first, second, or last third of a

race. Next to each corner I noted how

many corners were left in the race.

Corners are where resources are spent, so knowing how many corners

is left compared to how much wear an AO has left is an alternate way to figure

out what part of the race that strategy should be in.

For most of the race my Even strategy will spend resources depending on if the car has more resources then the number of corners remaining. That way, the car spends resources pretty evenly through out the race. On the other hand, the Back S strategy will spend very few resources before the 2nd third of a race.

Obfuscate

If I know what the AO is going to do before the AO does it, that

AO will be a lot less effective. This

will be more or less true depending on the level of player interaction. If there is little player interaction, you

might be able to skip this step. If

there is a lot of player interaction, this step is crucial to creating a

competitive AO.

Randomness is your friend here. Each AO should have at least 2 things it

might do on a given turn, or two ways it might do those things. This way, human opponents are not completely

sure what it will do. Be careful not to resolve that randomness until you absolutely have to -- right

before the AO needs to take an action or figure out if they will take an

action.

But don’t take the randomness too far unless that is the

actual strategy. You want the choices an

AO takes to make sense for its strategy.

The choices may just be slight variations of each other. They probably should not be completely

opposite.

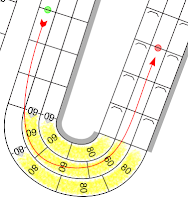

CFR Example

I made sure that each AO in

CFR had a choice between at least two different decision trees during each

phase of its strategy. Often this was

just a reordering of choices or a slight variation. After every corner you roll dice to re-pick a

decision tree for the next corner.

On the right you can see a sample phase from CFR's Front A strategy. Each line is essentially a decision tree giving the car 2 to 4 different choices for how many resources to spend in the next corner. In turn this will determine the car's speed.

The choices at the top direct the car to spend more then the ones further down until the stars indicate that those resources will only get spent if the use is particular efficient use.

Simplify then Cheat

After all of this, your AOs are likely bad at the game and

your decision trees are so complicated that it takes twice as long to take an

AO turn as a real turn.

Go back over your decision trees and simplify them. Then do it again. Pay particular attention to anything you had previously done to obfuscated or randomize AO actions. Does the obfuscation or randomization make it more time consuming to play an AO turn then a human turn?

Now find ways to have your AO "cheat". Cheats can do three things: speed up AO play,

make AOs harder opponents, and give AOs more character.

For instance, consider some mechanics that might take a

while to resolve. Having an AO always

succeed at performing one or more types of actions will speed up play, make them better at the game, and reinforce

their personalities and strategies.

Having an AO "cheat" more or less will also make some AOs better than

others.

CFR Example

Originally, I obfuscated too much. The symbols I used in decision trees had little relationship to the choices they represented. I eventually switching to symbols that better represented the action desired, were easily remembered, and required less translation.

Basic AOs in CFR are

passable, but to create challenging AOs I added a number of "cheats."

Many get bonuses during

set-up. This is my main method for

creating some AOs that are harder than others. A normal set-up in CFR uses 2 points to build a car. Stirling Moss' car, shown on the right, uses 4 points including some options (9 wear per lap) that are beyond what is normally available.

All of the AOs in CFR can

auto-pass certain die rolls during the game.

This is mostly a time-saver, but also clearly gives them some

advantages. Normally skill is used as a die roll modifier that helps drivers temporarily improve their car's performance. Historical Drivers use skill to automatically pass those same die rolls.

Finally, many have special

abilities or bonuses that reinforce their character and strategy but also give

them advantages. Stirling Moss can effectively use 3 wear in a corner, which is illegal for anyone else.

Diversify Your AOs

Look at your AOs. Are

there parts of each that can be swapped into another similar AO to create

something new? That’s a great way to

generate a lot more AOs then you thought you had.

For instance, maybe you built 3 AOs that are variations on a

military strategy. Each has a slightly

different set-up and slightly different decision trees. If you separate the set-ups from the decision

trees and randomly recombine them before each game you now have 9 different AOs, where you used to have 3.

Or maybe you find that you can split each AO’s decision

tree into 3 parts. Now you have 3 early

game decision trees, 3 mid game decision trees, and 3 late game decision trees for

each military AO creating even more variety and obfuscation.

CFR Example

In CFR I created 10

different decision trees (strategies) and 24 different set-ups (drivers) that come with in-game "cheats." Each set-up uses one of three

different decision trees.

This went through many changes during testing. Originally, I had 12 generic strategies that were married to particular set-ups. Then I separated set-ups from strategies and was able to reduce both the number of strategies and set-ups but still retained a lot of variety.

Conclusion

The most important part of designing AOs is the same as all

game design: testing. Very few games come with Automated Opponents. So there is a lot of space to practice using

the games already on your shelf.

I’ve started designing AOs for one of my son’s and my old

favorites, Valley of the Mammoths. I’ll

share the results of that project when I’m done. Below is what I ended up with for CFR (development, not final version).